The Rosenberg Trial: A Tale of Espionage, Family Betrayal, and the Fight for Justice

In the early 1950s, one of the most infamous espionage trials in American history unfolded: the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

Accused of spying for the Soviet Union and passing atomic secrets, the couple's case would become a symbol of Cold War paranoia, family betrayal, and a debate over justice.

The couple was convicted and sentenced to death, with Julius executed in 1953 and Ethel a few months later.

But decades later, many questions remain.

Were the Rosenbergs truly guilty, and if so, was Ethel's role as sinister as portrayed?

The Allegations Against the Rosenbergs

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were accused of espionage for the Soviet Union during a time when America was gripped by fear of Communist infiltration.

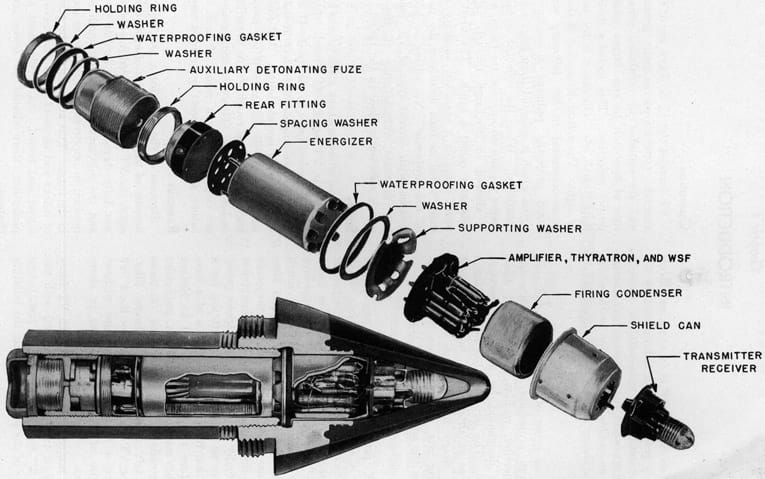

The trial, which began on March 6, 1951, revolved around allegations that Julius had leaked vital information about military technology, including radar, sonar, jet propulsion systems, and most controversially, the proximity fuze—a "super weapon" that could alter the course of warfare.

This small radar fuze, when attached to artillery shells, could detonate upon proximity to an enemy aircraft, significantly increasing its effectiveness in anti-aircraft defense.

Julius Rosenberg’s espionage activities went beyond simple theft of military secrets; he was said to have actively recruited a network of spies, both within the U.S. government and the scientific community.

He allegedly handed over classified information about the Manhattan Project and other top-secret military technologies to Soviet handlers.

According to Soviet accounts, Julius not only provided crucial information like the proximity fuze but also recruited others, some of whom became pivotal figures in the Soviet military-industrial complex.

Ethel's Role: A Matter of Debate

Ethel Rosenberg's involvement in her husband's espionage activities is still a subject of debate.

While Julius was the focus of the prosecution, Ethel was also charged with conspiracy and aiding and abetting espionage.

Her conviction was largely based on the testimony of her brother, David Greenglass, who claimed that Ethel typed up notes for Julius.

The most damning evidence against her came from Greenglass’ testimony, which painted her as a willing accomplice in her husband's espionage activities.

But was she really involved, or did she become a convenient scapegoat?

In recent years, declassified documents and new revelations have cast doubt on Ethel's guilt.

A 2024 memo released by the National Security Agency (NSA) noted that Ethel was not engaged in espionage work for the Soviet Union.

A top US codebreaker who decrypted secret Soviet communications during the cold war concluded that Ethel Rosenberg knew about husband Julius’s activities in atomic espionage but “did not engage in the work herself

The document, written a week after her arrest, reviewed the decrypted Soviet intelligence and concluded that Ethel’s involvement, if any, was limited.

This new evidence suggests that her role may have been exaggerated, possibly due to the fact that she was Julius' wife. T

he pressure to convict both of them may have led to her being implicated in activities that, in hindsight, appear far less concrete.

The Key Witness: David Greenglass

The prosecution’s case rested heavily on the testimony of David Greenglass, Ethel's brother, who admitted to passing military secrets to the Soviet Union.

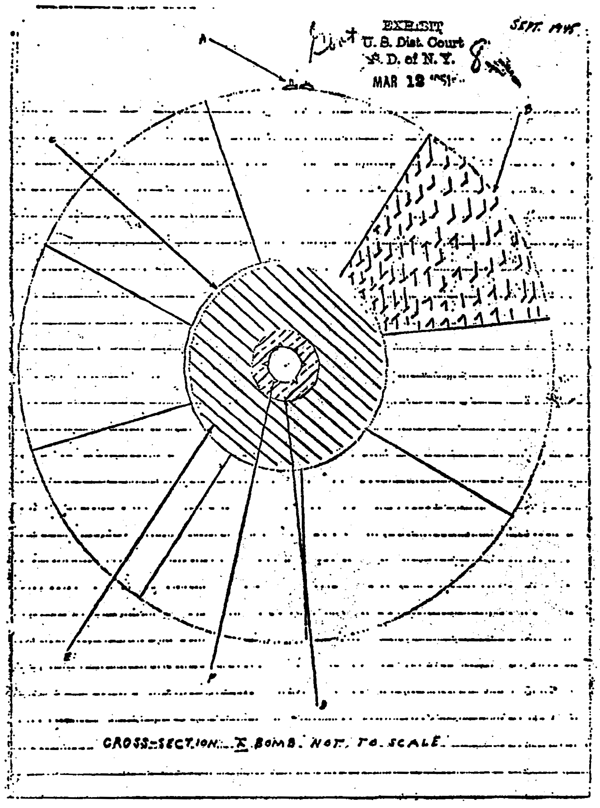

Greenglass was an Army engineer working on the Manhattan Project, and he revealed that he had shared a sketch of the "Fat Man" bomb—one of the two nuclear bombs dropped on Japan—with Julius Rosenberg.

It was this sketch that would become a central piece of evidence in the trial.

Greenglass's testimony was pivotal in securing the Rosenbergs' conviction, but it also raised questions.

Greenglass had a personal motive: his wife, Ruth, was also implicated in the espionage ring, but in exchange for his cooperation with the prosecution, he was promised a more lenient sentence.

Many believe that Greenglass’s testimony was shaped by this deal and that he may have exaggerated Ethel’s role to protect his own wife.

It’s important to consider that Greenglass's confession was made under pressure, and he later admitted that his testimony about Ethel’s involvement was likely exaggerated.

The Prosecution's Case: A Rush to Judgment

The U.S. government's decision to pursue the death penalty for the Rosenberg, especially Ethel, has been widely criticized.

While Julius was clearly a Soviet spy, the evidence against Ethel was scant and circumstantial.

Her role in the espionage activities seemed to be based mostly on her familial connection to Julius and the perception that, as his wife, she must have been complicit.

Her defense attorney, Emanuel Bloch, argued that the prosecution had no clear evidence to convict her, but his arguments fell on deaf ears.

Interestingly, the trial highlighted the imbalance of justice during the Cold War.

While Julius Rosenberg was accused of providing critical information to the Soviets, the government’s focus on his espionage activities overshadowed the reality that many others had engaged in similar behaviour with far less severe consequences.

For example, Klaus Fuchs, a British physicist who provided the Soviets with detailed information about nuclear weapons, was sentenced to just 14 years in prison, serving 9 years before being released and allowed to emigrate to East Germany.

In comparison, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were sentenced to death, with no chance of parole.

The Venona Project and the Declassified Evidence

After the fall of the Soviet Union, declassified documents, including the Venona transcripts, shed new light on the Rosenbergs’ activities.

Venona was a top-secret U.S. government project that decrypted Soviet communications, revealing Soviet spies in the U.S. government and military.

While Julius Rosenberg’s name appeared frequently in these transcripts, there was little mention of Ethel.

Some historians argue that this suggests Julius was the mastermind behind the espionage ring, while Ethel may have been more of a passive observer, unaware of the full scope of her husband’s activities.

The Venona transcripts also confirmed Julius’s significant role in recruiting spies within the U.S. military-industrial complex, many of whom went on to help the Soviet Union develop its own nuclear weapons.

One of the most chilling revelations was that Julius had handed over information on the proximity fuze, which would later play a crucial role in Soviet air defense.

But again, these revelations focused mainly on Julius, not Ethel.

Revisiting the Guilt of Ethel Rosenberg

As more information comes to light, it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain that Ethel Rosenberg was anything more than an unwitting accomplice, or perhaps even a victim of her husband’s espionage activities.

The lack of concrete evidence against her, combined with the new documents released in 2024, suggest that Ethel may have been unfairly convicted.

The prosecution's reliance on her brother's testimony, and the absence of any real proof of her involvement in espionage, makes her guilt far more uncertain.

Ethel’s execution in 1953 remains one of the most controversial aspects of the case.

Many believe she was sentenced to death because of her association with Julius, while others argue that she was targeted to send a message during a time of heightened fear and anti-Communist sentiment.

Conclusion: A Trial That Haunts American Justice

The Rosenberg trial was a landmark moment in the Cold War, a time when paranoia about Communist infiltration led to the erosion of civil liberties and a rush to judgment in high-profile cases.

While Julius Rosenberg’s guilt as a Soviet spy seems clear, Ethel’s role remains murky.

The trial and execution of the Rosenbergs left a stain on American justice that still lingers today.

New evidence continues to emerge, and while it may never provide definitive answers, it has forced us to reconsider the fairness of their convictions and the true nature of Ethel Rosenberg’s involvement.

The case serves as a powerful reminder of the dangers of guilt by association, the importance of due process, and the perils of state-sponsored fear.